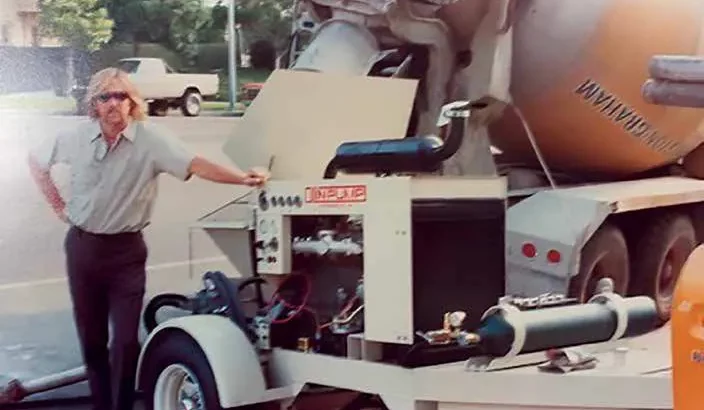

Dave Swain, the founder of Olin Pumps in Southern California, has been a tinkerer with motors since he was a kid. He started working on cars, then graduated to modifying, then designing and eventually building his own branded pumps that can pump mixes traditionally thought to require a concrete line pump (which he also manufactures in many sizes). But as he will tell you, so does every other pump manufacturer, so his line of ball-valve pumps is what sets him apart from the rest.

He commands a loyal following among people across the United States who contact him for advice about using pump, advice that he freely gives, whether you own one of his pumps or not. It’s hard to tell which is greater- the breadth of his knowledge, gained over 48 years in the concrete pumping business, or his enthusiasm for the machinery that he says is capable of more things than most people realize.

How did you get started?

I grew up near L.A., and I was always into cars and mechanical stuff. My first job was at a company that manufactured aluminum fuel tank trucks. I was just 15 and it was a summer job, but I learned how to weld on it, to the point where my high school shop teacher had me teach the welding.

My first full-time job was at a construction materials supply yard owned by a large masonry contractor on the West Coast. It was an easy job, working outside in the California weather loading bloc, cement and sand but what I wanted was to an equipment mechanic, particularly in the field. I got my wish as a “yard wrench,” and when the field guy got canned, the equipment manager got me the field job. I loved it. I visited all the job sites and got to see how things came together in commercial construction.

One day, I had just finished swapping out the torque converter in a Champ forklift with a Chrysler Slant 6 engine. I slid out from under it and was wiping the grease off my hands while watching a little ball-valve grout pump, either a Tommy Gun or a Giant (we had both brands), chugging away pumping high-lift grout up a few lifts. I stood there watching, thinking that’s pretty cool. They’re pumping solids, gravel and sand, through pipe and hose!

That was the beginning of the track my life has been on.

My dad was in the industrial rubber business, and he knew the owners of probably every pump company in L.A., as well as the OEMs Thomsen and Whiteman, who he sold wire braid hose to, before swivel joints came along, as well as squeeze tubes to Challenge Cook. I told him how interested I was watching that grout pump run, and he said he had a customer who might have a job for me.

Bill Hostetter owned A&B Concrete Pumping in Eagle Rock. He also had designed and manufactured his own ball valve manifold system to retrofit to Thomsen grout pumps, the A4 and A4.5, so that they would pump a wider variety of mixes. That little pump was very limited as to what it could pump, and the Mayco C-30 pump was kickin’ their butts. Bill was indeed looking for a welder- mechanic to assemble and install the MagnaFlo manifold, as well as someone to maintain his own fleet of pumps, and he also wanted to get me in the field as an oiler on his boom pump, and possibly run a spare pump and truck he had as a backup.

I started building the manifold kits and did maintenance on his pumps. I pumped concrete for him, as well. He gave me an old pump and truck, an old turquoise Ford F-100 short bed that had a Thompson 8.4 with a little 18-horse, two-cylinder Wisconsin engine. But I’d go on a job site and get the job done, and customers would request me. Before long, I was pumping all day, and at night I’d do the welding, installations and repairs.

One day, Bill comes driving in to the shop with a brand new F-350 cab and chassis, and proceeds to inform me that I have a new project. Thomsen had just introduced a brand new pump, the A7, to compete with the C-30, but it was a disaster. It cost a few people their jobs, as a matter of fact. So Bill purchased one without the manifold or hopper and instructed me to mount it on the truck, and design and build from start-to-finish a manual stick boom, water tank, bed, toolboxes and paint. When finished, the other employees, including his son, were anxious to see who was gonna get it is as their new pump. Bill handed me the keys and shook my hand, and said I’d earned it, not only because I built it, but because I had been doing all the most challenging jobs with the least capable pump. Needless to say, I wasn’t very popular from that day forth.

I did well with Bill, learned the fundamentals, as well as what he believed a ball valve should look like. I, on the other hand, was convinced that Mayco had a better idea, but it needed some grooming.

In the early ’70s, the president of my dad’s company purchased Airplaco in Cincinnati, an old company that manufactured gunite equipment. Airplaco had a ball-valve pump, a copy of the Thomsen A4.5 grout pump, that needed to be updated to be competitive in the marketplace. He approached me about coming to work for him. As much as I respected and appreciated Bill, the thought of learning about how a manufacturing business operates sounded pretty exciting. I hated leaving Bill and the job I loved so much, but I moved on and headed to Cincinnati. I bought the manifolds from Bill, so there would be no hard feelings, and beefed up the driveline. I’d build a pump, sell it to a gunite contractor, drive it to the customer anywhere in the country, design a shotcrete mix, teach the crew how to pump, nozzle, cut and trim shotcrete instead of gunite, pick up the check, drive back to Cincinnati, and repeat.

What made you decide to go out on your own?

My boss wanted me to go back to school and get my engineering degree. He’d say, “If you have an engineering degree, it makes you so much more valuable. I’ll pay your full salary and your school costs.”

I’d go, “No, I’m not that kind of engineer. I engineer with my gut and common sense. It’s about concrete and the physics of pumping it, which I teach myself. The rest is basic high school geometry. No, thanks.” He wouldn’t let me experiment with other stuff. I thought Bill’s manifold was okay, but I had other ideas about how to make ball-valves pump much more than watereddown sandy mixes.

So I started Olin Engineering in 1975. Olin is my middle name. It sounded a lot better than David Engineering or Swain Engineering. It had a Scandinavian ring to it. Made me sound like I was bigger than I was.

I was building drive lines to bolt into Mayco and Thomsen pumps and giving the customer a lifetime guarantee on it. The original drive lines were built to break. The biggest complaint about those pumps was their high maintenance. Joe Schmidt, a salesman for Thomsen, started referring customer to me. He’d say, ”There’s a young kid who builds a drive line upgrade with different pistons that increases the production rate. He has his own manifold, and it’s guaranteed for life.”

And word spread.

You said that you had a moment when you realized your purpose.

Yeah. All this time, I was modifying existing pumps to make them perform better. But I thought, ”You know, I really need to improve this industry. I need to build pumps that are going to pump real structural concrete and give small-line pumping a better reputation.”

One day, a customer by the name of Frank Uribe came to me and asked, “Why don’t you make your own pump? You know way more about it than that guy does.” I said, “I don’t know, it seems like a lot of time to build my own pump.” He said, ‘Well, for the time you spend fixing up brand new ones, you could be building your own. What do you think it would cost to build a 60-yph [cubic yards per hour], narrow ball-valve pump that could do rip-rap, shotcrete and sand slurry?”

I just kind of grabbed a number out of my — and said, “I don’t know, eighteen thousand dollars?” He got out his checkbook, wrote a check on the spot and said, “Build me one.”

And that’s how the first Olin-Pump came along.

When Frank took delivery of his pump, guys came out to watch it run, and next thing you know they were writing me checks. This was in 1980, right when we were going into a recession. Not many people were buying equipment, so it was really hard getting started. But I’d saved money, and I kept working on it and improving on it and the pumps we’ve got now are pumping mixes that a couple decades ago could only be pumped by small swing-tube pumps through 2½-inch line, and we’re pumping them with our ball-valve pumps, depending upon gradation, from 15-1900# of ½-inch minus per yard, or a¾ blend mix, 800# ¾, 800# 3/8, and even 110# lightweight, all through 2½-inch line.

Were those the years when you made your reputation?

My customers in the early ’80s were all union pumpers doing parking garages and other pouredin-place structures. We would pump concrete straight up 37 stories, 4,000 or 5,000 PSI four-inch slump structural mix for vertical walls and columns with high steel density. We’d use three-inch pipe, going to 2.5-inch on the deck, and they’d roll s caffolding around and pump right into the top of the form.

The big pumps couldn’t handle that kind of work, because a big pump can’t pump through a small line. A pump with 10-inch cylinders doesn’t like reducing down to small line.

My early pumps were 60 yph, and I had customers going out and selling general contractors on commercial jobs with a plan to bring out two of my pumps, convert to pea gravel mix, and run two crews simultaneously, each running 2½-inch hose.

That strategy helped the contractors outbid the guys with the boom pumps, and it really had a lot of people pissed off at me.

I used to build a slide-valve pump, because I was always a fan of the Schwing gate-valve pump, but I didn’t like the way it had four separate valves. So I built a gate-valve pump with one valve and only two cylinders. I spent years developing it. It would pump mixes that other pumps, even boom pumps couldn’t. It liked a lean, rocky mix. That was back when we were building nuclear power plants and bridge decks with 1 ½- to two-inch aggregate. It would pump it, and it was smooth like a ball-valve, but it was expensive to build and it didn’t like fine mixes.

“I engineer with my gut and common sense. It’s about concrete and the physics of pumping it, which I teach myself. The rest is basic high school geometry.”

Tell me about the First Interstate job.

In the 1990s, the old First Interstate building in L.A. caught fire, and the fire gutted three or four floors around the 15th floor. It inspired the movie Towering Inferno.

One of my customers came to me and asked, “Can we pump 90-pound structural lightweight up 15 stories?” That’s structural lightweight concrete that only weighs 90 pounds per cubic foot when it’s cured and air dried, as opposed to 150 pounds for hard-rock concrete. And it’s what the contract called for since the steel building was engineered for that weight.

All the pumps companies said, “It’s impossible, you should have looked into it before you bid the job.” My customer asked if we can do it, and I said, “I don’t see why not. Just because no one’s done it before doesn’t mean it can’t be done.”

We came up with a mix design that everybody approved, and I told the customer, “Look, we’re going to use the slide-valve pump and set up all five-inch system. No four-inch whip at the end. I don’t want any reduction at the end of the line.”

When word got around that my customer was going to do it with one of my trailer pumps, the pumping industry in L.A. was rather amused by it. The night of the pour, I get up there, everything’s set up, and we had an audience of every pump company owner in town, and wouldn’t you know it, Bill Hostetter.

A tough crowd. They’re all standing behind the barricades watching, and here I was, this young kid. And they weren’t rooting for me.

I put on my hard hat and glasses and said, “I’ll run the pump and once we get going, you guys can take over from there” – I think it was a 600-yard pour the first night – “and I’ll come back for the washout.”

We got the concrete trucks, and put in two yards of slurry to prime it. I climbed the ladder to look at the mix. The deputy inspector checked it out and signed off on it. I got on the walkie-talkie and said, “Here we go.”

We started pumping, and in a minute or two, the guys up in the building said, “We got mud, shut it off.”

I shut the pump off, idled the motor down, and all those company owners looked at each other like, “What the —- just happened?” They shook their heads and walked away.

I didn’t think it was any big deal. You set it up right and use common sense. I knew it was important to keep the pressure off the mud, make sure the aggregate was fresh out of the factory, and it had all the water it needed in it. We just did it by the book.

What does the future hold for you?

Well, I’m 67 and I love what I do but I don’t want to do it forever. I own property and a home in Prescott, Arizona and enjoy spending time there. I plan on retiring there.

My whole life has been concrete pumping. As far back as I can remember, I’ve had potential buyers approach me for acquisition, but it’s got to be the right fit. What I’ve learned over 48 years will be hard to pass on to someone in a short time, so I need to get started.

I love sharing my experiences and the knowledge it’s provided me.

I build one-inch concrete pumps, and ball-valve pumps, and there are so many things that OlinPump ball-valve pumps will do that people still don’t believe.

Republished from Marine Construction Magazine Issue V, 2022