NTSB Accident Brief

On September 8, 2019, at 0355 local time, the towing vessel Savage Voyager and its tow of two loaded tank barges were engaged in southbound locking operations at the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, six miles from Dennis, Mississippi (all miles given in statute miles).

After lock operations began, the bow of barge PBL 3422 contacted the lock’s upper gate sill and was hung up as the water level dropped, resulting in hull failure and a cargo tank breach. About 117,030 gallons (2,786 barrels) of crude oil were released into the lock. No injuries were reported. The damaged barge cost $402,294 to repair, and costs to return the lock to service 18 days later were about $4 million.

Background

The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, which opened in 1985, joined the Tennessee River in northeast Mississippi with the Tombigbee River in west-central Alabama. The waterway’s navigation channel was 234 miles long and 300 feet wide, with minimum depths of 12 feet in the divide and canal sections and 9 feet in the river section. The waterway’s 10 locks provided a total lift/descent of 341 feet, and each lock’s chamber was 600 feet long and 110 feet wide. The waterway was used to shorten shipping distances from many inland ports to the Gulf Coast (instead of transiting on the Mississippi River).

Operated by the US Army Corps of Engineers, the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam, located at mile 411.9 of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, separated the Tennessee River Basin from the Tombigbee River Basin and formed Bay Springs Lake. Construction on the lock was completed in 1983. Originally named the Bay Springs Lock & Dam, the lock was renamed in 1997. At the time of the accident, the lock’s 84-foot maximum lift/descent was the fourth highest in the United States, and its chamber held about 52 million gallons of water. During locking down operations, 46 million gallons of water were discharged in 13 minutes.

Accident Events

The Savage Voyager was an 83.5-foot-long towing vessel built in 2014 and originally named the Elizabeth P. Settoon. In 2017, Savage Inland Marine bought the vessel and renamed it. The twin-propeller towing vessel was powered by two diesel engines for a total of 2,400 horsepower.

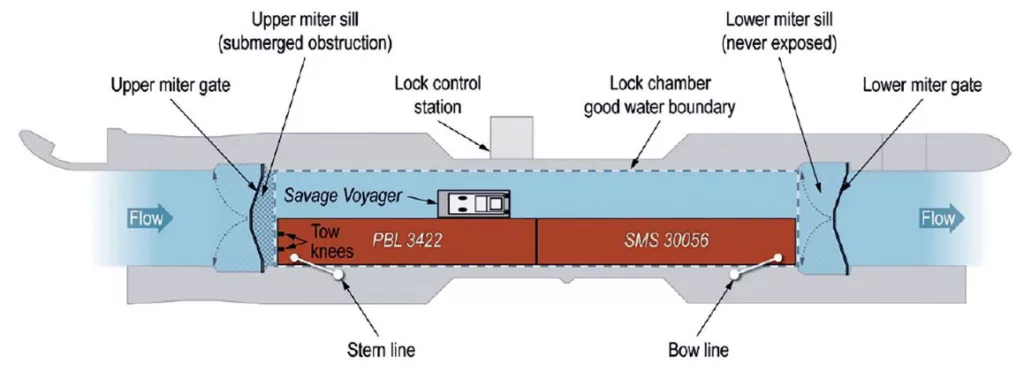

On September 4, 2019, the Savage Voyager’s crew loaded crude oil onto the vessel’s tow of two tank barges, the SMS 30056 and the PBL 3422, at the Omega Facility located at mile 196.3 of the Upper Mississippi River in Hartford, Illinois. According to the towboat’s deck log, 20,309.6 barrels (853,003 gallons) were loaded onto the SMS 30056, and 20,260.6 barrels (850,945 gallons) were loaded onto the PBL 3422. At 1620, the Savage Voyager tow got under way southbound, en route to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The vessel had six crew members on board, including a captain, pilot, two tankermen, and two deckhands. The barges were secured in a line, stern to stern (rakes out), with the SMS 30056 forward and the PBL 3422 aft, pushed by the Savage Voyager. The towboat was drawing 10 feet, and each barge was 297.5 feet long with a beam of 54 feet, giving the tow a total length of 678.5 feet, a maximum beam of 54 feet, and a maximum draft of 10 feet.

During their 28-day work rotation on board, the six crew members were split into two watches of 6 hours on/6 hours off, with the captain or pilot, a tankerman, and a deckhand on each watch. On September 7 at 2300, the pilot and the accident deckhand and tankerman came on watch, and the pilot reported that operationally, “everything was as it should be.”

By 0330 on September 8, the Savage Voyager and its tow had arrived at the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam on the southern end of Bay Springs Lake, Mississippi. The pilot stated that he radioed the lock operator to request permission to conduct downbound locking operations, and the on-watch tankerman and deckhand went to the port and starboard forward corners of the forward barge SMS 30056 with fenders in hand.

(To lock downbound, a vessel enters the lock from the higher elevation of the lake. The lock operator then closes the upper gates and begins locking operations, during which the lock’s water level decreases to the level of the river below. Once the water level has lowered, the lock operator opens the lower gates, and the vessel exits the lock.)

According to the lock operator’s log, about 0345, he granted the pilot permission to enter the lock chamber, and the pilot maneuvered the tow through the open upper gate and into the lock chamber with the assistance of the tankerman and deckhand, who both relayed the tow’s distance from the lockwall and the distance into the 600-foot-long-by-110- foot-wide lock chamber over VHF radio to the pilot in the wheelhouse.

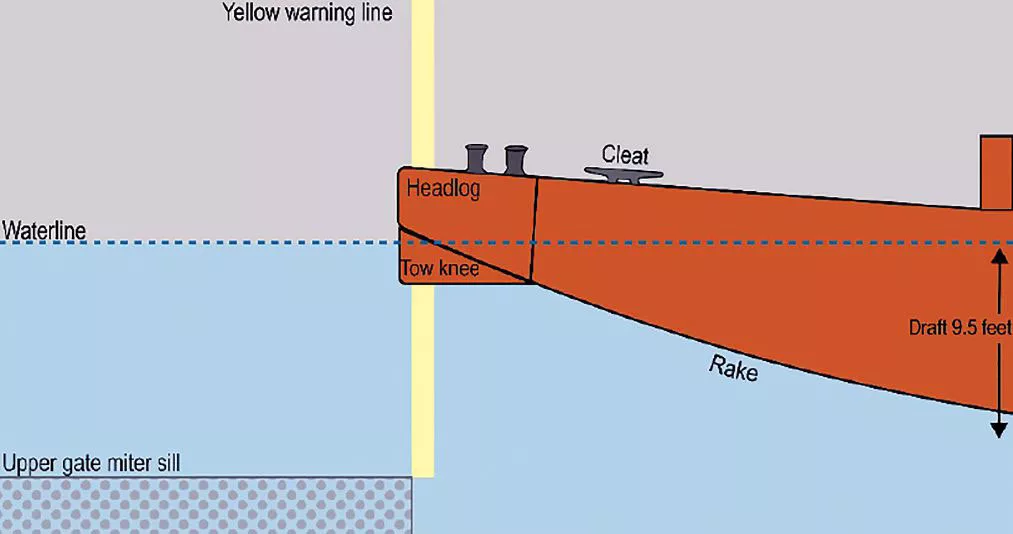

The Corps of Engineers standard operating procedures required that all tows entering locks on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway use two lines (one forward and one aft) to secure a tow before locking. At the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam, the lock chamber— that is, the area in which the tow could safely conduct locking operations—was demarcated by a yellow warning line (a vertical line measuring 12 inches wide painted on the lock wall) at the upper gate’s concrete miter sill, and a sign at the lower gate’s miter sill that denoted “600 feet.”

Once the Savage Voyager’s two barges were “in position” (in accordance with instructions from the lock operator) within the lock chamber, with their starboard sides to the lockwall, the tankerman on the forward barge secured an aft-leading bow line from the lock’s floating mooring bitt to a deck cleat on the SMS 30056. The deckhand on the aft barge secured a forward-leading stern line from another floating mooring bitt to the deck cleat on the PBL 3422. The lock’s floating mooring bitts could travel freely in a vertical direction up or down the lock wall with the level of the water in the lock. Both crew members radioed the pilot once their respective lines were secured. The pilot stated that he visually verified from the wheelhouse that the PBL 3422’s rake was clear of the upper gate’s yellow warning.

Since the length of the Savage Voyager tow measured 678.5 feet, the towboat would not fit in the lock chamber positioned behind the aft barge. The crew was therefore required to complete a “knockout” lockage in which the Savage Voyager would be positioned next to the tow (the two barges measured a combined 595 feet long) in the 600-foot-long lock chamber. (A “knockout” lockage is necessary when the length of a tow exceeds the length of a lock chamber. During the “knockout,” the tow is reconfigured so that the towboat is positioned alongside the tow.) The deckhand released the Savage Voyager from the tow, and the pilot positioned the tug’s starboard side alongside the PBL 3422. The deckhand secured lines from the towing vessel to the PBL 3422 and returned to his position on the rake of the PBL 3422 to tend the tow’s stern line; he stated that the barge “didn’t move” during the maneuver, and “if it wasn’t where it’s supposed to be, I would have seen it.” The tankerman also reported that there was no shifting of the barges. The pilot stated that he kept the starboard engine in neutral and the port engine ahead in order to keep the Savage Voyager tight alongside the barge.

Once the pilot saw that the deckhand had returned to his post on the PBL 3422, he radioed the lock operator to inform him that the crew was ready to commence lock operations. The lock operator stated he looked at the lock chamber’s camera feed to “make sure that he’s on the inside of the line.” Once he was satisfied, he closed the upper gate, then closed the fill valves and opened the emptying valves so that the water level began to drop. During the locking—a total descent of 83 feet at the time— the deckhand (on the rake of the PBL 3422) and tankerman (on the rake of the SMS 30056) were responsible for tending their respective lines to keep the tow within the lock chamber.

The deckhand stated that “maybe a couple seconds after … water had begun to come out of the chamber,” he noticed that the PBL 3422 had “touched” and was hung on the concrete miter sill. He radioed the pilot in the wheelhouse to inform him that the tow was stuck and to “push ahead on it,” then radioed the tankerman to “give [him] some slack in that head line” so that the tow could move forward. In the wheelhouse, the pilot throttled both engines full ahead in an attempt to free the barge and heard “a loud noise.” About 0355, the pilot sounded the general alarm and radioed the lock operator to alert him of the situation and request that he stop the locking process.

After hearing the pilot over the radio, the lock operator looked out the window of his station, saw that the rake of the barge was about three feet out of the water, and immediately began closing the valves to stop the water from lowering in the lock chamber. He radioed the pilot to inform him that it would take a few minutes for the valves to close and he could not stop the water from lowering until the valve stop sequence completed. As the water continued to lower in the lock chamber, the rake of the barge was held in place while the rest of the barge descended, and the rake bent 45 degrees

The tankerman radioed the deckhand and told him to “get to safety,” so the deckhand ran forward toward the Savage Voyager. As the deckhand stepped onto the Savage Voyager, the PBL 3422’s rake end slipped from the concrete miter sill and dropped into the water. After the valves were closed, the water level was about 13 feet below the concrete miter sill.

The captain, who was off duty at the time of the accident, came up to the wheelhouse and called the company and US Coast Guard to report the accident. The crew mustered on the bow of the Savage Voyager (the tankerman initially remained on the SMS 30056, since he was afraid the lines connecting the two barges would fail, but later joined the crew on the towboat’s bow). The two deckhands and two tankermen replaced two lines (one between the barges and one between the Savage Voyager and the PBL 3422), which had parted during the accident. While they were replacing the lines, the crew noticed crude oil spilling from the PBL 3422 into the lock chamber and reported it to the captain and pilot in the wheelhouse. The captain and pilot shut down the vessel’s engines and ventilation to stop vapors from the crude oil from entering the wheelhouse, and the crew took shelter within the Savage Voyager.

The captain contacted the lock operator to report strong fumes in the lock chamber and to request the water level be raised so that the crew would not have to climb as far up the lockwall ladder to evacuate from the tow. After the water level was raised, all six Savage Voyager crewmembers evacuated the vessel by climbing onto the lockwall ladder and out of the chamber. No injuries were reported.

After the accident, the Coast Guard closed the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway between miles 410 and 414, and initiated efforts with Tishomingo County Emergency Management to contain the crude oil that had continued spilling into the lock. A sock boom was placed 100 feet downstream of the lower gate to contain any oil that might seep through the gate. Later in the day, at 1419, a vacuum truck arrived on scene to conduct cleanup operations. By 1530, oil was no longer spilling into the lock chamber. The Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam was closed for 18 days (until September 25) while it was decontaminated and cleaned.

On September 9, the Savage Voyager’s crew transferred approximately 4,338 barrels of crude oil from the PBL 3422’s damaged tank 1 to the SMS 30056; about 13,135 barrels of crude oil remained in the PBL 3422’s undamaged tanks 2 and 3. Approximately 2,786 barrels (117,030 gallons) of crude oil had been spilled into the lock, and an estimated 22 barrels (942 gallons) were unrecoverable.

About a week later, on September 15, another company towing vessel, the Savage Innovator, arrived on scene with another tank barge, the SMS 30037. The damaged tank on the PBL 3422 was patched, and, with oil containment booms in place, the decontaminated tow was made ready to move out of the lock. On September 17, the remaining oil on the PBL 3422 was transferred to the SMS 30037, and the Savage Voyager and its tow were shifted out of the lock to a secondary containment area for final decontamination. After decontamination was completed on September 19, the Savage Voyager departed the lock with the SMS 30056 and SMS 30037 en route to Tuscaloosa to discharge its cargo. On the same day, the Savage Innovator departed the lock with the PBL 3422 en route to New Orleans, Louisiana, to repair the damaged barge. The total cost to clean the lock and tow was over $4 million.

Additional Information

Damage. On October 28, 2019, the barge PBL 3422 arrived at a shipyard and repair facility in Harvey, Louisiana, where its damaged bow was removed and extensive sections on the port- and starboard-side shell plating (forward of the collision bulkhead) were replaced. The weather deck plating aft of the collision bulkhead, sections of the bottom shell plating, the deck plating forward of the collision bulkhead, and the cargo tank top plating were also replaced. The repairs cost a total of $402,294.

Personnel. The Savage Voyager’s pilot had been credentialed for 22 years and had been employed at the company for six months. The tankerman had been employed at the company for over two years, and the deckhand for about one year. All three crew members typically worked on the Savage Voyager and had transited the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam numerous times as part of a routine voyage. Post-accident toxicological testing of the three Savage Voyager crew members involved in the accident was negative for drugs or alcohol.

The lock operator had over 30 years experience in his position. His work/rest history showed that on September 4 and 5, he had worked from 0800 to 2000. He was off duty on September 6. The following day, he awoke at 0600, and his shift began at 2000 and was scheduled to end at 0800 on September 8. The lock operator participated in random drug testing as part of his job requirements, but after the accident, he did not undergo toxicological testing because his supervisor believed the lock operator had not “done anything out of the ordinary for lockage.”

Lockage Procedures. According to Title 33 Code of Federal Regulations 207.300, the lock operator was “charged with the immediate control and management of the lock” and was responsible for ensuring that “all laws, rules, and regulations for the use of the lock and lock area are duly complied with.” The regulation also gave the lock operator the authority “to give all necessary orders and directions in accordance therewith,” and stated that “all vessels … shall be moored as directed by the lockmaster.”

The Corps of Engineers’ Lock Operator Training Manual stated that the lock operator should “direct vessel operators to the areas in which the vessels or tows are to be moored and will not close the lock gates until all vessels are properly moored.” The manual further stated the lock operators should not “operate the filling or emptying valves until satisfied the tow or craft is properly moored.”

Vessels in the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam were required to be moored with bow and stern lines leading in opposite directions in order to prevent the vessel from “running” in the lock. The Corps of Engineers reported that since the lower gate miter sill remained submerged during locking operations, it was not unusual for tows to moor barges using the first few feet of water beyond the lower gate miter sill—which was marked by a sign denoting the end of the 600-foot lock chamber—but there were no written instructions to towboat operators allowing its use. The pilot stated that he was unaware that this was allowed and he had only crossed the sign in the past when he was instructed to do so by the lock operator.

The lock operator’s lock control station had a video monitor that showed (at an angle) the yellow warning line. The warning line was obscured below the staff gauge at 25 feet by a handrail. The Corps of Engineers reported that shortly after a tow began to descend, the lock operator could not see a barge’s bow on the monitor after it dropped below 25 feet on the staff gauge, and therefore could not view its position relative to the warning line.

According to the Corps of Engineers, once a lock operator began the procedure to open the valves, discharge sirens automatically sounded, not as a warning for the crew, but to warn vessels downstream that the lock was about to discharge water in their direction. The Savage Voyager’s deckhand reported that lockages usually “come with a siren . . . I wait on the siren, and then that’s when the locks usually proceed,” but on the day of the accident, he did not hear one. The Corps reported that the sirens were operational on the day of the accident.

After the accident, the Corps of Engineers conducted a timed test at the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam to determine how quickly the lock’s water level dropped once locking began. The Corps reported that with a full chamber, it took three minutes and 58 seconds total from the start of the test until the water level dropped 23 feet from the upper pool to the top of the upper gate’s concrete miter sill (two minutes and 15 seconds for the emptying valves to fully open from their closed position, and an additional 1 minute and 43 seconds for the lock chamber’s water level to drop to the miter sill). Once the miter sill was visible, the Corps began closing the lock’s emptying valves to determine how long it would take to cease locking operations. The Corps reported that it took two minutes and 11 seconds for the valves to fully close, during which time the water level continued to drop before stopping about 13–14 feet below the top of the upper gate’smiter sill.

During 2018, the Corps of Engineers reported that the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam conducted 1,329 commercial lockages, averaging 110 per month, with no commercial lockage accidents. Of those lockages, 512 (39 percent) were knockout lockages similar to the accident lockage; 125 of these knockout lockages took place between 0100 and 0500, all without incident.

Analysis

At the time of the accident, the Savage Voyager and its crew were on a routine voyage pushing two tank barges from Hartford, Illinois, to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. All three on-watch crewmembers had previously transited and performed knockout lockages at the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam (and other locks on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway) on the Savage Voyager with the same towing arrangement. It is therefore unlikely that the crew’s inexperience with locking procedures led to the accident.

The deckhand and tankerman followed the Corp of Engineers’ standard operating procedures and used two lines (one forward and one aft) to secure the two barges inside the lock chamber. The deckhand stated that after the crew “knocked out” the Savage Voyager and secured the tow alongside the barges, the PBL 3422’s stern line was secure and the tow had not crossed the yellow warning line that marked the upper gate’s submerged miter sill. With the Savage Voyager at the barge’s side, the tow’s length was reduced to 595 feet, and in the 600-footlong lock chamber, the crew had only five feet of clearance in which the tow might safely move, leaving a very small margin of error and requiring the deckhand and tankerman to closely watch their respective lines.

Locking operations began with about 23 feet of water above the upper gate miter sill (and 23 feet on the staff gauge), and the lock operator stated that he verified that the tow’s placement was within the yellow warning line at the time the locking process began. However, at some point during locking, the PBL 3422 crossed the warning line, placing the tow in danger of contacting the miter sill. The Corp of Engineers’ post-accident testing showed it took a combined 3 minutes and 58 seconds for the water level to drop to the sill. The PBL 3422’s tow knees were 1.6 feet below the surface of the water; therefore, a 21.4-foot drop would likely have resulted in contact with the sill. With the water lowering at a calculated average rate of about 1 foot every 10.3 seconds, less than 30 seconds after locking commenced and the emptying valves began to open, the lock operator would have lost visual of the tow, since the main deck would have dipped below his video camera. After about 3.7 minutes, the barge’s tow knees would have contacted the sill.

The deckhand stated that he noticed the barge was stuck “maybe a couple seconds after . . . water had begun to come out of the chamber.” However, it would have taken over 3 minutes after lock operations began for the barge to contact the miter sill, indicating that it is unlikely that the deckhand was attentively minding the stern line. Additionally, the tankerman was not aware that the vessel was out of position until the deckhand radioed him. Had the deck crew been vigilantly monitoring the vessel’s position, they would have noticed the barge was out of position before it became stuck on the sill and could have alerted the pilot.

Once the PBL 3422’s rake became hung on the concrete miter sill, the deckhand notified the pilot, who sounded the towboat’s general alarm about 0355 and radioed the lock operator to request he halt the locking process. The pilot also attempted to mitigate further damage to the barge and pull it off the sill by throttling both engines full ahead. However, since it took over two minutes for the emptying valves to fully close, the water continued to rapidly descend in the lock chamber, and the barge became hung on the sill, bending the rake and breaching the forward cargo tank before dropping into the water.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the contact of the Savage Voyager’s tow with the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam was the tow moving out of position in the lock chamber while locking down when the crew did not effectively monitor and maintain the vessel’s position during its descent, resulting in the aft barge becoming hung on the upper gate miter sill. Although locking operations can seem routine, the margins for safety are frequently low. Maintaining vessel position and communication with the lock operator are critical practices to ensure safe lockage. Crews should avoid complacency and vigilantly monitor lines at all times to prevent “running” in a lock.

Republished from Marine Construction Magazine Issue V, 2022