Marine construction relies on the skill and experience of divers who perform challenging tasks in zero visibility, connected to the surface by a hose. Most of the divers don’t want to do anything else.

Here’s the simple truth about commercial diving: No part of marine construction is so important yet

seen by so few people as is the underwater work of commercial divers.

In a marine environment—coastal, inland or deep-water—tasks that are routine on dry land often have to be performed in water where often the professionals doing the work can’t see beyond their hands—working in “zero vis,” to use the industry term. That makes construction underwater anything but routine, even if the procedures and safety routines to be followed are practiced and discussed before “getting wet,” to use another industry term.

Although commercial diving is becoming safer, thanks to technology and safety standards set by coordinated industry self-regulation, working as a commercial diver is still a life of calculated risk. But most commercial divers wouldn’t want to do anything else.

“I was a water bug as a kid,” says Kevin Todd, the owner of KT Divers near Austin, Tex., “and I also was a really good welder by the time I was in seventh grade. Everyone said, ‘hell, you oughta be one of those underwater welders.’ So I went to a commercial diving school, and started my career with a company called American Oilfield Divers in 1989. I did it for many years, kinda retired from diving for a little while to do construction. Once we started KT Waterfront, I basically branched off and formed a division, KT Divers. I still do quite a bit of diving, but we also have staff and freelance divers.”

What tasks commercial divers perform when they’re underwater is almost limitless. The services that KT Divers lists on its website include barge and rig support, welding, inspection, salvage, debris removal, ultrasonic thickness testing and zebra mussel control.

“There’s no one specific thing we do,” Todd says. “It’s equally balanced between construction, salvage and inspections. Right now, we don’t a lot of offshore oil and gas because of slowed demand, but there’s strong demand for docks on the lakes near where we’re based. Most of our jobs are inshore and in our region right now.”

Contractors tend to look local first, but will go further afield during an emergency that requires rapid response. Commercial diving companies learn to be ready to leave on a moment’s notice.

“We could get a call to go New York or Washington state tomorrow, or off to Idaho and to do a dam inspection,” he says. “We’ve got the equipment and vehicles to travel anywhere.”

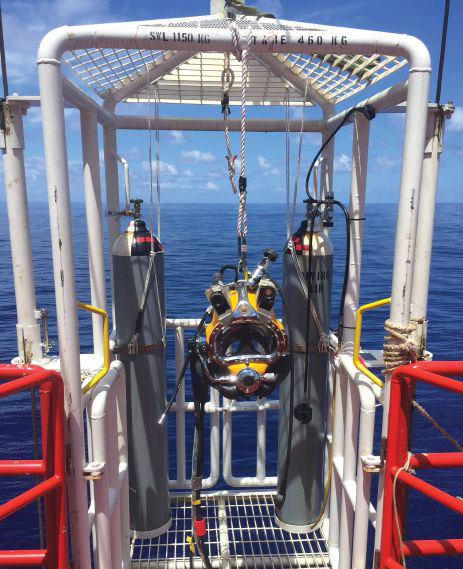

It takes a long apprenticeship to become a commercial diver. The modern diver works inside a suit that is connected to the deck of a boat by an umbilical cord – the hose – that supplies oxygen, power for headlamps and video cameras, and most importantly, two-way voice communication with the “tender,” the person who is monitoring every aspect of the diver’s lifeline.

“You start by going through a commercial diving school program,” Todd says. “If you want to work offshore, you’re going to work as a tender for two to four years. If you go to work for some of the smaller, inland companies, though, you can get wet right out of the gate.”

A tender is someone “topside”—on the deck of the dive boat who tends the diver’s hose, monitoring oxygen and other gauges and making sure the equipment’s running right. “Typically, on a commercial diving job site, you’re going to have a dive supervisor, as well as tenders and divers. The tenders are green, but they’re learning. It takes a little bit of time.”

Commercial diving has a certification structure akin to that of welding. Although most states do not require either a welder or a diver to get a license (New York state is the big exception), certification by a professional association is virtually a requirement.

The professional association for diving, and the government agencies that employ divers, work closely to create the industry standards. The Association of Diving Contractors International (ADCI) publishes the International Consensus Standards for Commercial Diving and Underwater Operations, the bible for the industry. In turn, the ADCI works closely with the Association of Commercial Diving Educators (ACDE) to develop teaching standards. OSHA’s standard 29 CFR Part 1910, Subpart T – Commercial Diving Operations is written in coordination with both associations, as is the U.S. Navy Diving Manual.

According to Phil Newsum, ADCI’s executive director, “Certification in the United States is issued by ADCI and recognized by the Coast Guard, the Army Corps of Engineers and OSHA. We are a trade association and private, and we have memos of understanding with the CG and industry.

“And in order to get our certification,” Newsum adds, “you have to be formally trained. The standard for that training is the ANSI/ACDE Minimum Standard for Commercial Diver Training.” Enrollment numbers at commercial diving schools have been pretty consistent, Newsum says. “Like a lot of other trades. when the economy is good, trade schools have good attendance,” he explains. “In addition, a lot of people leave the industry. They go in thinking it’s gonna be a certain way, and find out it’s harder than they thought. You’re away from home a lot. The attrition rate for the first two years of a diver’s career can be 65-70 percent. After that it’s more stable, but people also age out or get into operations management.”

Newsum echos Kevin Todd’s description of where the work is.

“Because of pricing in the oil industry, diving in support of oil production is down from where it was 10 years ago,” Newsum says, “but we’re seeing an increase in work for the inland sector—dams, bridges, ports and ship husbandry.”

According to Wikipedia, “[In the] U.S. Bureau of Labor occupational employment statistics for May 2019 for commercial divers (excluding athletes and sports competitors, law enforcement personnel, and hunting and fishing workers), national employment estimate is 3,420 employees, at a mean annual wage of $67,100 and mean hourly rate of $32.26 for this occupation, Actual rates can vary from about half to about twice these figures. Employment is concentrated in coastal states. These figures are slightly higher than for 2017.”

What the figures don’t report is that in the view of many in the business, commercial diving is getting more efficient and safer.

Jorge Gonzalez, co-owner of Sea Divers in Miami, started in 2015. As much as 75 to 85 percent of his work is construction-related. “We do a lot of underwater welding and ‘burning’ [cutting steel], as well as concrete work, inspections and relocating coral for new construction.” Gonzalez’s crews follow standard diving safety protocols. “We do our pre-dive check-up and meeting, with the crane operator if a crane’s in use,” he says. “Safety means constant communication between the dive tender and the diver. The tender is watching the gauges and the hose. You don’t make any movement around heavy equipment and cranes without the tender talking to the diver and crane operator.”

The dive supervisor leads the pre-dive meeting, and it’s up to him (or her) to evaluate conditions such as weather, water clarity and currents.

“On a day-to-day basis, the decision as to whether conditions are safe for diving is up to dive supervisor,” says Kevin Todd. “If it’s offshore and we’ve got six or eight-foot seas, the dive supervisor’s gonna say, ‘it’s not safe to dive today, we have to call it.’

“Inland is a whole different animal than offshore. Offshore is gonna be, what are we doing, what is the weather like, what are the depth and currents. Inland work is actually more dangerous, though, because typically, you’re dealing with a lot more black water and a lot more moving parts. Are we in a ship channel with constant traffic? Are we work- ing on vessels or moving equipment that needs to be locked out for partial pressures? Even if it’s shallow work, there’s greater potential for danger.”

Whether working in the open ocean on a deepwater oil exploration tower or in a busy ship channel of a port, the keys to safety are preparation and communication, experts agree.

“There still are incidents, based on things like different pressures, equipment failure from non-inspection, but the volume is substantially lower than, say, 20 years ago,” says ADCI’s Phil Newsum. “A lot of things contribute to greater safety. One is that it costs too much not to be safe. The last thing a contractor wants is to be taken to civil court. There’s no ceiling to liability, especially if negligence can be proven.”

Technology also has contributed to safety. “The equipment is basically the same, but manufacturers are looking at life support features. New helmets, regulators and masks have all kinds of redundancy and easier ways to check that they’re working properly.”

But in the end, Newsum adds, “the biggest safety issue is to make sure that equipment is serviced regularly by qualified and certified individuals.”

Other technology has improved efficiency. Better, wearable sonar has made working in tannin-stained black waterless “diving by braille,” although it won’t help a diver see through mud.

“Working by feel and touch is still really how it works today,” says Kevin Todd. “But every bit helps when you working in hazardous environments like pump stations, power plants, and pressure differentials.”

Improved hot-water diving suits for winter work are a less noticed but greatly appreciated (by divers, at least) technology. A water feed is added to the hose that circulates water heated topside through the diving suit.

“They’re like night-and-day from early 2000s,” Todd says. “It’s like working in a warm bathtub. Divers can spend a lot more time in the water because they’re not freezing.”

Experience, training and planning, everyone interviewed for this story agreed, are the elements of a successful diving career. And not coincidentally, they’re what divers recommend that potential clients look for when considering hiring a company to perform underwater construction work.

“Look for a commercial diving outfit, rather than a scuba store,” says Kevin Todd. “I don’t want to discount scuba, which can be useful in some areas. If the project doesn’t need surface supply, you don’t need to move thousands of dollars of equipment. But in a lot of cases, clients hire an outfit that’s not seen what can go wrong when you don’t have communication with a tender. Almost all commercial diving is surface supply and constant communication. You can hear them, and they can hear you.

“The key is to plan and look for the best way to accomplish what you need done,” Todd continues. “What’s the best way to do something, in terms of both safety and cost.”

For the professionals who follow those principles, commercial diving is beyond a job. It’s a vocation. In the words of Jorge Gonzalez of Sea Divers in Miami, “I consider myself one of the lucky ones to have a business doing something I love.”

Republished from Marine Construction Magazine Issue V, 2022