On January 12, 2021, about 2359 local time, the towing vessel Robert Cenac was pushing one empty barge when the barge struck the CSX railway Rigolets swing bridge, located about 11 miles southeast of Slidell, Louisiana. No pollution or injuries were reported. Damages to the bridge and barge were estimated at $1.1 million and $5,000, respectively.

BACKGROUND

The 56.5-foot-long Robert Cenac, a twin-propeller towboat, was constructed of steel and built in 2014. It had two steering rudders and two flanking rudders. The vessel was owned by Al Cenac Towing LLC. At the time of the accident, the Robert Cenac was pushing a single empty hopper barge, SH 238, which measured 195 feet long by 35 feet wide. Overall, the length and width of the tow was 251.5 feet by 35 feet, and the deepest draft was that of the Robert Cenac, which was about 6 feet. The Robert Cenac had a crew consisting of a captain, a pilot, and two deckhands. (Aboard towing vessels on inland waterways, pilot is a term used for a person, other than the captain, who navigates the vessel.) Each worked a 6-hours-on/6-hours-off rotation. The captain worked the midnight to 0600 and noon to 1800 watches together with a deckhand, and the pilot worked the 0600 to noon and 1800 to midnight watches with the other deckhand.

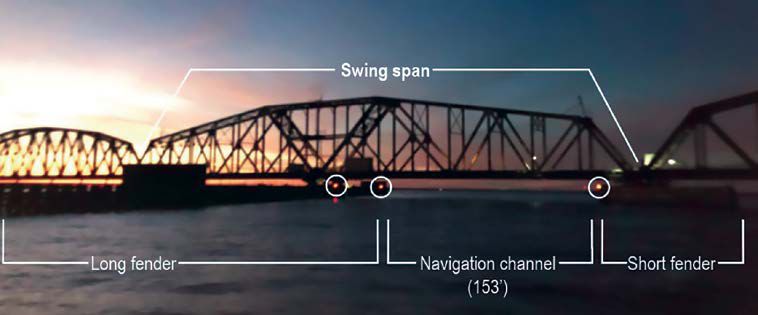

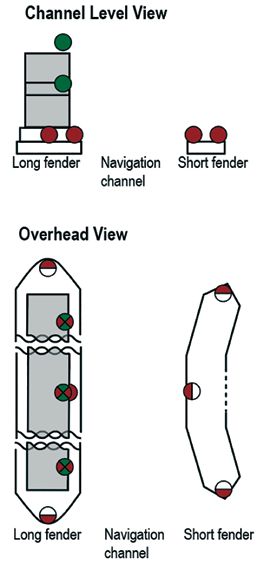

The CSX Transportation Rigolets swing bridge number 34 (Rigolets Bridge), owned, operated, and maintained by CSX Transportation, carried one main track of railroad across the Rigolets Pass on the southeastern side of Lake Pontchartrain. Built in 1928 and constructed of riveted steel, the bridge had an 11-foot vertical clearance over the water. The 414-foot, hydraulically operated swing span opened in a clockwise direction (and closed in a counterclockwise direction, as viewed from above) by rotating horizontally on a central axis (a concrete pier). In the open position, the swing span would be in a generally northwest (302°) to southeast (122°) orientation. The permanent navigation channel through the bridge, between the long (southwest) fender protecting the swing span and a short fender on the northeast side of the channel, was 153 feet wide.

Drawbridge regulations contained in Title 33 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 117 included general requirements for drawbridges (subpart A) and bridge-specific requirements for individual bridges (subpart B). The regulations required land and water traffic to pass over or through the draw (swing span) as soon as possible to prevent unnecessary delays in the opening and closure of the draw. Subpart B did not contain any specific requirements for the Rigolets Bridge. The bridge was continuously attended by a bridge operator (tender) located in a bridge house on the north side of the track about 350 feet from the short fender. When the bridge was closed, a vessel operator could contact the bridge operator by VHF radio, whistle, or visual signal to request it be opened. The bridge operator’s ability to open the bridge depended on train traffic, and the bridge took about 12 minutes to open fully. Although there was no policy or guidance for bridge operator radiotelephone communications with vessels, the bridge operator on duty at the time of the accident said that he would only inform a requesting vessel that the bridge was clear to pass through after confirming the bridge was fully open.

At the time of the accident, the captain of the Robert Cenac said that there was a flood tide, and, in those conditions, there would be a cross current setting from east to west when approaching the bridge from the south. According to the United States Coast Pilot Volume 5, “Currents are very irregular…They set with great velocity through the Rigolets at times, and especially through the draws of the bridges. Velocities of… 3.8 knots [4.4 mph] at the railroad bridge have been observed. At the railroad bridge westerly currents set west-southwest onto the fender on the southwest side of the draw, and easterly currents set east by north onto the fender on the northeast side.”

The Coast Pilot also stated, “the bridge should not be approached closely until the draw is opened, and then only with caution.”

ACCIDENT EVENTS

On January 12, about 2139, the Robert Cenac tow got under way from Heron Bay, Mississippi, at mile 44 on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway east. The tow proceeded westbound toward the intersection of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and the Rigolets, where it was to pass through the Rigolets Bridge bound for Port Bienville, Mississippi, to work a dredge operation.

About 2231, near mile 38, the pilot of the Robert Cenac (on watch at that time) informed the Rigolets Bridge operator by radio that the vessel was 30 minutes away inbound and requested the bridge be opened. The pilot recalled the bridge operator saying there were two trains that had to pass before the bridge could be opened, so the pilot reduced the speed of the tow from about 8 to 4 mph. About 2253, at mile 36.5, he steered the tow out of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway toward the Rigolets Bridge, about 2.4 miles ahead, and then brought the engines to idle. He explained to investigators that “you can’t just sit there a thousand feet away and wait for the bridge to open,” and that the tow should be kept “at least two miles away” to properly line up to pass through the bridge to account for any set from the current and effects of the wind once the bridge was open.

At 2306, the Robert Cenac tow was holding about 1.5 miles southeast of the bridge, awaiting further communication from the bridge operator. The pilot noted that the current was setting the tow to the west and he would have to clutch in reverse to keep the tow in a position to line up to pass through the bridge.

While holding, the pilot of the Robert Cenac saw the lights of both trains as they passed over the Rigolets bridge. According to CSX train movement records and signal system data logs, the status of the Rigolets Bridge track circuit changed from “occupied” to “unoccupied” at 2334, indicating the rear of the second train was off the bridge. Sometime after 2330, the captain of the Robert Cenac arrived in the wheelhouse and began a watch handover. The pilot informed the captain that they were holding and waiting for the bridge operator to call back to announce the bridge was open. Having seen both trains pass, the pilot called the bridge operator over the radio and asked if the bridge was open. The pilot said he heard a reply of “cap, where are you at?” He told the bridge operator, “I’m sitting here waiting on you, about 15 minutes away.” According to the pilot, the bridge operator replied, “I’m gonna get it open for you, cap.” After that, around 2345, the captain took the helm from the pilot, who went below to the galley. The captain told investigators that, at the time he took the watch, the Robert Cenac was holding, and he was aware that they were waiting for the bridge to open. Shortly after taking the helm, the captain said that “at some point” he received a call from the bridge operator informing him that the bridge was open. At 2348, according to the Robert Cenac’s electronic chart system playback recording, the Robert Cenac began to make headway toward the bridge. Anticipating a westerly set from the current, the captain said he set up against the current, approaching the span at an angle, lining up as he had previously done under similar conditions, “a little to the east.” He noted that there were “hardly any lights” on the bridge, and he could see only two red lights on the long fender wall. About a half to a quarter mile away, he used the spotlight on top of the wheelhouse to look for the bridge fendering.

At 2355, the head of the tow was about 2,300 feet from the bridge (2,000 feet from the southern end of the long fender), and the tow was moving at a speed over ground of 6.9 mph and a course over ground of 306°. The captain recalled that, with the spotlight pointed toward the head of the barge, he could see the fendering, and he started to line up the tow to pass through the opening. The captain told investigators that, as the tow got closer to the long fender, he saw the swing span was not fully open as he said he had been informed and was overhanging the long fender “looking as if it was three-quarters of the way open.” He told investigators that by the time he noticed the bridge protruding outside of the protective fender and began to back down (full astern), the tow was too close to stop, as the current set the tow toward the span.

At 2358, the tow was at a speed of 7.1 mph; less than a minute later, the speed of the tow began to rapidly decrease. About 2359, the coaming on the forward port side of the barge struck the overhanging south (when open) end of the swing span. The bridge operator told investigators that, while his hand was on the lever opening the bridge, he saw on the closed-circuit television camera the Robert Cenac tow “shooting the gap… a couple of seconds” before the barge hit the span.

The pilot, who was in the galley at the time of the accident, said he felt a bump and went up to the wheelhouse. When he got there, he saw that the barge had come away from the swing span, which continued opening. He recalled hearing the bridge operator say over the radio, “alright cap, the bridge is fully open,” which the pilot said led him to believe that the bridge operator was not aware the barge had hit the swing span. He then heard the captain reply, “yeah, I hit the bridge.”

Investigators asked the bridge operator to clarify details of the communication between him and the Robert Cenac. The bridge operator said he told the Robert Cenac’s captain he was starting to operate the bridge and that he would let them know when it was fully open and clear to come through. The bridge operator told investigators that he did not communicate that the bridge was fully open, and when the captain told him the tow had hit the bridge, he replied, “I was still operating the bridge and it wasn’t fully open and I didn’t clear you to come through yet.” He said he heard the captain of the Robert Cenac say that he “had a guy on the barge that told him the bridge was open and so he came through.” In statements given to the US Coast Guard, none of the Robert Cenac’s crew said they were on the barge.

The captain positioned the tow up against the long fender and called company personnel and the Coast Guard to report the casualty. Upon confirmation that the bridge was struck, the bridge operator notified the rail dispatcher to stop any train traffic bound for the bridge. At 0037, the Robert Cenac got back under way toward its destination of Port Bienville. Once the tow was clear, the bridge operator tried to close the bridge, but it would not close completely.

Additional Information

There were no known or reported deficiencies with the Robert Cenac’s navigation, communication, steering, or propulsion systems at the time of the accident. There were no audio recordings available for the VHF communications between the pilot and captain of the Robert Cenac and the Rigolets Bridge operator. The bridge operator control station had closed-circuit television cameras but no recording capability.

Post-accident alcohol and other drug testing was conducted for the captain of the Robert Cenac with all results negative. The bridge operator for the Rigolets Bridge was not required to be tested for alcohol and other drugs.

The captain of the Robert Cenac had 20 years of experience as captain of towing vessels and said he was very familiar with the area that he was operating in and had passed through the Rigolets Bridge, at night, “quite a few times.” With the set of the current from east to west the night of the accident, he said he lined up for the approach as he normally had done for similar conditions and said he would have changed nothing about his approach to the bridge or the speed of the vessel.

The Rigolets Bridge operator began his 8-hour shift about 2200. He told investigators that there were no problems with the bridge hydraulic and electrical systems and that he checked the fender navigation lights and saw that they were operational. CSX required that bridge operators record time, direction, and name of vessels passing through bridge openings. Although the bridge tender said he performed this task, CSX did not provide investigators any of these records from January 7 to the date of the accident.

Bridge Lighting

According to 33 CFR 118.70, swing spans of through bridges should be lit so that, when viewed from an approaching vessel, a closed swing span will display three red lights on top of the span structure, one at each end of the span on the same level and one on top at the center of the span, and an open swing span will display three green lights, one at each end of the span and one on top at the center of the span. Swing bridges are also required to be lighted so that each end of the piers adjacent to the navigation channel or each end of the protection piers (fenders) protecting the bridge’s pivot point is marked with a red light.

The Robert Cenac captain described seeing only two lights on the long fender and one on the short fender as the tow approached the channel to pass through the bridge, where there should have been three on each. Post-accident video and pictures of the Rigolets Bridge confirmed the captain’s observations: there were no lights marking the south end of the short fender and long fender. The swing span was not fitted with alternate green and red navigation lights marking each end and the top center of the bridge span. No correspondence was found from the Coast Guard exempting the Rigolets Bridge from the requirements of 33 CFR 118.70.

The last CSX bridge inspection report for the Rigolets Bridge was completed about 3 weeks before the accident, on December 7, 2020, and documented one missing solar navigation light on the long fender; there was no further documentation regarding its repair or replacement status. Additionally, damage was documented on the short fender on the upstream (north) side due to a recent vessel contact, and the long fender was missing about 12 boards on the downstream (south) side of the dolphin due to a recent storm.

Damage

The damage to the forward port side of the barge SH 238 consisted of indentations and cracks to the portside forward bow and portside forward hopper coaming, which cost an estimated $5,000 to repair. The captain told investigators the Robert Cenac never struck any part of the span or fendering, and there was no damage to the towing vessel.

The Rigolets Bridge sustained damage costing about $1.1 million. A third-party post-accident survey report stated that the Robert Cenac tow initially struck the south end of the bridge’s opened swing span, veered off the swing span, and then collided with the north side of the bridge’s short fender, causing damage to the north side of the short fender and the south side of the long fender. The survey also reported that “the tug’s stern likely contacted the bridge’s south side/long fender in way of the center pivot pier” and that damage to the fenders “appeared to be newly sustained.” Another post-accident survey report documented that the south end (in the open position) floor beam of the swing span/bridge “was directly impacted approximately four feet from the inside edge of the west truss.” There was damage to the swing span structure and components, the assembly used to open and close the swing span, and electrical and cabling components. Evidence markings were found on the north main pinion, indicating the span was struck “near the bridge fully open position.” After repairs were made, the Rigolets Bridge was restored to regular service on March 2, 2021.

Post-accident Actions

Post-accident, CSX installed additional white flood-type lighting to illuminate the bridge and the channel. The pilot of the Robert Cenac told investigators that, during later transits through the bridge, the additional lighting made it easier to identify the opening. As of this report’s issue date, the swing span of the Rigolets Bridge remains without navigation lighting as required by regulation.

According to Coast Guard records, there were 29 incident investigations related to vessel contacts at the Rigolets Bridge from 1994 to the accident date. Of those, 18 were contacts with the fendering system, and 7 were contacts with the bridge structure. Strong currents were a factor in 12 of the incident investigations. Records provided by CSX also documented a barge striking and damaging the swing span and long fender on January 4, 2020; the Coast Guard had no record of the incident.

ANALYSIS

The captain of the Robert Cenac was aware of the local current conditions. He described his approach to the bridge as normal, based on the westerly current set. Though he began to back down (full astern) once aware the swing span was not in the fully open position, he attributed the current as a factor for not being able to stop in time.

Bridge Navigation Lighting

The Robert Cenac captain did not see the Rigolets Bridge swing span, estimated three-quarters of the way open, extending past the fendering until, according to him, it was too late to stop the tow or maneuver it away. Investigators found that the swing span was not fitted with any navigation lighting, as required by regulation, to indicate that it was in the open or closed position. Both the captain and the pilot, who were experienced in operating tows through the bridge at night, told investigators that it was difficult to see the navigation channel through the bridge fenders. The captain saw only two red navigation lights on the long fender, and one on the short fender; no lights marked the end he was approaching. Investigators found that navigation lights were not located at the ends of the fenders as required by regulations. Had the swing span been fitted with the required navigation lighting (using red/green navigation lights on the bridge span), the Robert Cenac captain would likely have been able to visually determine the position of the swing span throughout its opening sequence as he made his approach. Thus, he may have opted to continue holding until seeing lights indicating the swing span was open, or, if approaching the bridge while it was opening, he would have likely seen a navigation light at the end of the swing span, prompting him to abort the approach while there was still time and distance to avoid hitting the span.

Vessel and Bridge Operator Communication

CSX records indicated the second train was clear of the Rigolets Bridge at 2334. Based on that time and the span’s opening time of 12 minutes, the earliest time that the bridge could have been fully opened would have been about 2346, roughly 12 minutes before the barge struck the span. While the pilot and the captain were changing the watch (sometime between 2330 and 2345), the pilot called the bridge operator to remind him they were still waiting and to ask if the bridge was opened; the bridge operator responded that he would “get it open.” Drawbridge regulations (33 CFR 117.9) require land and water traffic to pass over or through the draw as soon as possible to prevent unnecessary delays in opening and closure of the draw. The bridge operator attested there were no electrical or mechanical problems when opening the bridge. However, in this accident, the bridge operator did not immediately open the bridge after the second train had cleared the track circuit.

About 14 minutes after the second train cleared the track circuit, and after the pilot called to say the tow was still waiting, at 2348, the Robert Cenac captain started making his approach toward the bridge after he said he was informed the bridge was open. The bridge operator said his last communication to the Robert Cenac was that he would start opening the bridge and let him know when it was fully open and clear to pass through. The captain’s and the bridge operator’s accounts of the communication surrounding the accident differed. There were no audio recordings of or witnesses to the communications between the Rigolets Bridge operator and the Robert Cenac captain, and there was no evidence to determine with accuracy the context and timing of their communications.

The Coast Pilot noted, “the [Rigolets] bridge should not be approached closely until the draw is opened, and then only with caution.” The bridge was not fully open when the captain made his approach. Additionally, the captain stated that the bridge was poorly lit. Therefore, the captain should have verbally confirmed with the bridge operator that the bridge was open. Furthermore, the bridge operator should have called the captain via VHF radio if he saw the bridge was not all the way open as the towboat approached. This accident was an instance of poor communication; both parties were responsible for exercising good judgment and practices, and both should have exchanged clear and unambiguous requests, orders, or direction in an effort to execute the transit safely.

CONCLUSIONS

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the contact of the Robert Cenac tow with the CSX Rigolets railway swing bridge was the poor communication between the bridge operator and vessel operator. Contributing to the accident was the absence of bridge span navigation lighting that would have provided the vessel operator with a visual indication of the bridge’s opening status.

Lessons Learned: Communication Between Drawbridge Operators and Vessel Operators

Communication between drawbridge operators and vessel operators requesting bridge openings must be clear. Commonly used in all modes of transportation, closed loop communication, in which the sender confirms the message is understood or provides additional information or clarification, ensures the receiver understands the message.

Republished from Marine Construction Magazine Issue V, 2022